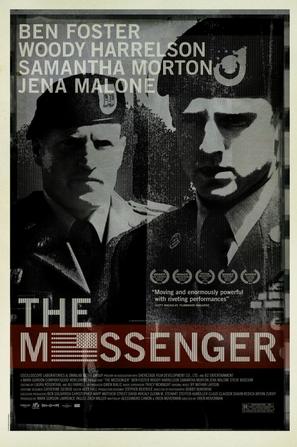

信使 The Messenger

Don't touch them. Don't hug them.

Don't get involved in any way.

Maybe the only way to do it is by the book. You walk up to the house of a total stranger, ring the bell and inform them that their child has been killed in combat. When they open the door and see two uniformed men, they already know the news. Some collapse. Some won't let you finish before they beat their fists on your chest, crying at you to shut up, god-damn it, that can't be true. Some seem to fall into a form of denial, polite, inviting you in, as if this is a social situation.

Some tell you it's a mistake. It isn't a mistake. "The Messenger" is an empathetic drama about two men who have that job. One is Capt. Tony Stone (Woody Harrelson), an old hand at breaking the news. The other is Staff Sgt. Will Montgomery (Ben Foster), who was wounded in combat in Iraq and is serving out the last three months of his tour. Stone, who has never experienced combat, is the more soldierly. Montgomery, in his first days on the job, has a tendency to care about the people --mostly parents -- he's informing.

That's a very bad idea, Stone tells him. It is always necessary to go by the book. Don't have physical contact with anyone, let along hug them. Better for you, better for them. These are their lives. They need the news, not a new best friend. Stone is another of Woody Harrelson's penetrating performances. With his hair shaved almost as short as a kid in boot camp, his eyes behind dark glasses, his manner displaying the stubborn fragility of the newly recovering alcoholic, he doesn't care that much about Montgomery, either. This may not be the first soldier he's had to break in on this hard assignment.

Ben Foster as Montgomery has usually played tough guys ("Alpha Dog," "3:10 to Yuma," the Alaskan vampire thriller "30 Days of Darkness"). It is a wonderment to me how some actors seem defined by their credits, and reinvent themselves in the right role. Here in countless subtle ways, he suggests a human being with ordinary feelings who has been through painful experiences and is outwardly calm but not anywhere near healed.

Both of them are time bombs. How close is Stone to taking another drink? Will post-traumatic stress syndrome bring down Montgomery? They drive in their rental car through the ordinary streets of America, so recently left by those they bring news of. Stone takes the lead. He sticks to the script. "The Secretary of Defense deeply regrets informing you that your (son, daughter), (military rank), (name), has been killed while on duty."

Everyone takes it differently, and the film develops the two characters as they meet survivors, notably Samantha Morton as a new widow, and Steve Buscemi as an angry father. Following the Army way, they would never see these people again. It doesn't work out that way.

Montgomery encounters Olivia (Samantha Morton) again. He sensed she was hurting. A tender, frightened romance slowly begins to grow between them, in a series of scenes that are not simply about two people but about these two, and all that we know about them and continue to learn. They meet the angry father again, and Buscemi, as he sometimes does, plays an almost impossible scene in a way that we couldn't anticipate and that could not be improved.

"The Messenger" is the first film directed by Oren Moverman, a combat veteran of the Israeli army, whose earlier screenplays included the Bob Dylan biopic "I'm Not There" (2007) and the extraordinary "Jesus' Son" (1999). This is a writer's picture, no less than a visual experience that approaches its subject as tactfully as the messengers do. No fancy camerawork. It happens, we absorb it.

An important element is Kelly (Jena Malone), the girl Montgomery left behind when he shipped out to Iraq. She hasn't remained committed. She isn't heartless; that's her trouble. Her heart found other occupations. Kelly treads a careful, not unkind, path with Montgomery. Her absence has created a vacuum; he may be too willing for Olivia to fill it.

"The Messenger" knows that even if it tells a tearjerking story, it doesn't have to be a tearjerker. In fact, when a sad story tries too hard, it can be fatal. You have to be the one coming to your own realization about the sadness. Moverman and his screenwriter, Alessandro Camon, born in Italy, have made a very particularly American story, alert to nuances of speech and behavior. All particular stories are universal, inviting us to look in instead of pandering to us. This one looks at the faces of war. Only a few, but they represent so many.