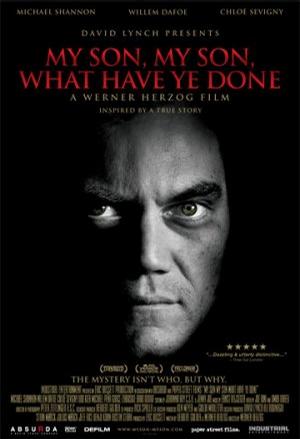

My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done

儿子,你都干了什么

The detective, the matricide and the ostrich

BY ROGER EBERT

Werner Herzog's "My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done" is a splendid example of a movie not on autopilot. I bore my readers by complaining about how bored I am by formula movies that recycle the same moronic elements. Now here is a film where Udo Kier's eyeglasses are snatched from his pocket by an ostrich, has them yanked from the ostrich's throat by a farmhand, gets them back all covered with ostrich mucus, and tells the ostrich, "Don't you do that again!"

Meanwhile, there is talk about how the racist ostrich farmer once raised a chicken as big as, I think, 40 ordinary birds. What did he do with it? "Ate it. Sooner pluck one than forty." Knowing as I do that Herzog hates chickens with a passion beyond all reason, I flashed back to an earlier scene in which the film's protagonist talks with his scrawny pet flamingoes. Is a theme emerging here? And the flamingo who regards the camera with a dubious look, is it doing an imitation of the staring iguana in Herzog's "Bad Lieutenant?"

For me it hardly matters if a Herzog film provides conventional movie pleasures. Many of them do. "Bad Lieutenant," for example. "My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done," on the other hand, confounds all convention and denies all expected pleasures, providing instead the delight of watching Herzog feed the police hostage formula into the Mixmaster of his imagination. It's as if he began with the outline of a stunningly routine police procedural and said to hell with it, I'm going to hang my whimsy on this clothesline.

He casts Willem Dafoe as his hero, a homicide detective named Hank Havenhurst. Dafoe is known for his willingness to embrace projects by directors who work on the edge. He is an excellent actor, and splendid here at creating a cop who conducts his job with tunnel vision and few expected human emotions. It is difficult to conceive of a police officer showing less response to a madman ostrich farmer.

His case involves a man named Brad McCullum, played by the inspired Michael Shannon as a man with an alarming stare beneath a lowering brow. He kills his mother with a wicked antique sword, as she sits having coffee with two neighbors. He likes to repeat "Razzle Dazzle," which reminded me of "Helter Skelter," and yes, the movie is "inspired by a true story." His mother (Grace Zabriskie) is a woman who is so nice she could, possibly, inspire murder, especially in a son who has undergone life-altering experiences in the Peruvian rain forest, as this one has--and why, you ask? For the excellent reason, I suspect, that Herzog could to great difficulty to revisit the Urubamba River in Peru, where he shot part of "Fitzcarraldo" (1982). Perhaps whenever he encounters an actor with alarming eyes, like Klaus Kinski or Shannon, he thinks, "I will put him to the test of the Urubamba River!"

Detective Havenhurst takes over a command center in front of the house where Brad is said to be holding two hostages (never seen), and interviews Brad's fiancée Ingrid (Chloe Sevigny) and his theater director, Lee Meyers (Udo Kier). Both tell him stories that inspire flashbacks. Indeed, most of the film involve flashbacks leading up to the moment when Brad slashed his mother. Ingrid is played by Sevigny as a dim, sweet young woman lacking all insight and instinct for self-protection, and Meyers is played by Kier as a man who is incredibly patient with Brad during rehearsals for the Greek tragedy, Elektra. That's the one where the son slays his mother.

The memories of Lee Meyers inspire the field trip to the ostrich farm run by Uncle Ted (Brad Dourif). If you've been keeping track, the film's cast includes almost only cult actors often involved with cult directors: Dafoe, Shannon, Sevigny, Kier, Dourif, Zabriskie, and I haven't even mentioned Oscar nominee Irma P. Hall and Verne Troyer. Havenhurst's partner is played by Michael Pena, who is not a cult actor but plays one in this movie. Little jest. For that matter, the film's producer is David Lynch, one of the few producers who might think it made perfect sense that a cop drama set in San Diego would require location filming on the Urubamba River.

There is a scene in this movie that involves men who appear to be yurt dwellers from Mongolia, one with spectacular eyebrow hairs. I confess I may have had a momentary attention lapse, but I can't remember what they had to do with the plot. Still, I'll not soon forget those eyebrows, which is more than I can say for most scenes at the 60% mark in most cop movies. I am also grateful for two very long shots, one involving Grace Zabriskie and the other Verne Troyer, in which they look at the camera for 30 or 40 seconds while flanked with Shannon and another one of the actors. These look like freeze frames, but you can see the actors moving just a little. What do these shots represent? Why, the director's impatience with convention, that's what.

I have now performed an excellent job of describing the movie. Can you sense why I enjoyed it? It you don't like it, you won't be able to claim I misled you. I rode on an ostrich once. Halfway between Oudtshoorn and the Cango Caves, it was.